Why “messy” matters permalink

For too long, we’ve treated math like it should always be neat, step-by-step, predictable, and efficient. But real math? Real math is messy. It involves uncertainty, iteration, and judgment. You try a path, learn something from it, and adjust.

When students only see polished final answers, they miss the thinking that got us there - the scratch work, the dead ends, the “wait… does this even make sense?” moments that are actually the work of mathematics.

What Students Really Need to See permalink

We need to pull back the curtain and show students our mess as teachers. Think aloud, explain your reasoning, and don't be afraid to work through problems with students. Celebrate the messy work of students, too!

When the emphasis is on the right answer, students begin to believe that speed = smart. That if they don’t know what to do immediately, they’re not “a math person.” But real problem solvers try ideas, evaluate them, and try again. That’s how things get built in medicine, engineering, data science, and everyday life.

What messy tasks unlock permalink

- Multiple entry points so every student can begin somewhere.

- Diverse strategies from visuals, tables, and graphs to computation and code.

- Meaningful scaffolds that respond to student thinking, not a scripted sequence.

- Identity & agency when students start to see themselves as mathematicians.

Fluency still matters. Students need tools to draw on, but if we only teach symbol pushing, we’re preparing them for a world where computers and calculators will always be faster. Thinking is the human advantage.

Contrived vs. real problems permalink

In much of the math instruction students experience, every number is clean and every path is prescribed. In real life, you estimate from imperfect information, you define reasonable assumptions, and you decide what “good enough” looks like. That’s modeling—and it’s the beating heart of mathematics.

Contrived → “The average teen sends 60 texts a day. How many in a year?” (a neat multiplication problem).

Real → “How many texts does the average teen send in a year?” Suddenly, students need to decide...

One of my favorite ways to bring this kind of problem into the classroom is with 3-Act Tasks (popularized by Dan Meyer). The structure is simple but powerful:

- Act 1: Pose a curious problem (often with an image or short video) and invite students to give an estimate. They share one they know is too high and one they know is too low.

- Act 2: Students ask for the information they need, and key pieces of data are revealed as they investigate.

- Act 3: The class works toward a solution and compares strategies.

I love 3-Act Tasks because they normalize uncertainty. Students start without everything they need, just like real problem solvers. They practice asking good questions, not just answering the ones we hand them.

I’ll dig more into inquiry-based learning in a future post, but if you’d like to explore 3-Act-Tasks right away, check out the resources linked at the end of this article.

Messy math doesn’t just live in classrooms. Even at the highest levels, mathematicians wrestle with uncertainty, chase ideas that don’t work, and circle back to try again. One of my favorite examples to share with students is Andrew Wiles, whose story shows that the mess is not something to grow out of—it’s part of how math works, all the way to the top.

Even Mathematicians Get Messy permalink

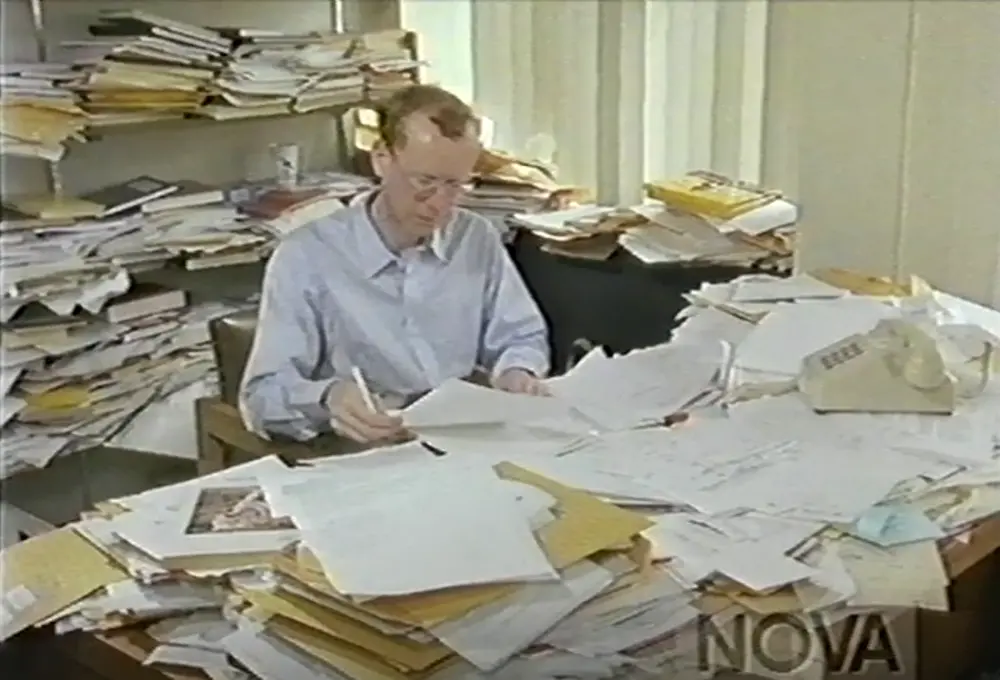

When I taught geometry, I used to show my students a clip from the NOVA documentary The Proof, which tells the story of Andrew Wiles, the mathematician who finally solved Fermat’s Last Theorem.

What struck me most was not just the brilliance of his proof, but the struggle behind it. For years he worked in isolation, chasing ideas that often collapsed. At one point, he thought he was finished—only for a colleague to find a flaw that forced him back to square one.

“The first seven years I’d worked on this problem I loved every minute of it, however hard it had been… there had been setbacks, often things that had seemed insurmountable.” — Andrew Wiles

Even his desk looked like math is messy—papers stacked high, drafts everywhere. And yet, out of that chaos came one of the most elegant proofs in history.

Andrew Wiles working on Fermat’s Last Theorem (screengrab from NOVA documentary The Proof, 1997)

I wanted my students to see this because it proves something essential: even the greatest mathematicians live in the mess. They erase, revise, and rethink. If Andrew Wiles can take years to find the right path, surely it’s okay if you have to cross something out in your proof.

If you’d like to watch the full documentary, it’s available through the Internet Archive. (When I first showed it, YouTube didn't exist, so I had to fast forward through a VHS copy.)

Ready to get messy? permalink

Let’s make room for uncertainty, estimation, and iteration. Let students see the mess, live in the mess, and learn from the mess. Because in a world full of calculators, thinkers will always stand out.

Try These Messy Math Resources permalink

- Tap Into Teen Minds (3-Act Math Tasks)

- Robert Kaplinsky’s Lessons

- Estimation 180

- Open Middle Problems (also from Robert Kaplinsky)

Subscribe below to be notified when new Solvefinity messy math lesson plans drop.